Fried rice is normally a popular choice among diners in Lagos, the economic capital of Nigeria. Yet lately many people have stopped ordering it, says restaurant manager Toni Aladekomo.

With the price of the dish shooting up to N4,000 ($5.20) from N1,500 a year ago, it has “stopped being affordable for most”, says Aladekomo, general manager of Grey Matter Social Space, a restaurant in the upmarket business district of Victoria Island.

In Nigeria, rice is the most commonly consumed meal — and the bedrock of the national dish jollof rice. But the price of 1kg of the imported grain was up by 46.34 per cent in August compared with the same period last year, according to the most recent data from the country’s statistics agency.

While prices have risen across the board as Nigeria grapples with its highest rate of inflation in two decades, the sharp increase in the cost of this everyday staple can be traced to a crackdown by India, the world’s largest rice exporter, in response to fears of a production shortfall and rising domestic prices.

It started last year when the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi imposed export restrictions on broken rice — a cheap variety imported particularly by poorer countries from Bangladesh to Benin — which is still in place.

By the end of July, India had banned exports of non-basmati white rice and followed this in August with a minimum sale price for basmati rice and a 20 per cent tariff on parboiled rice, extended until March.

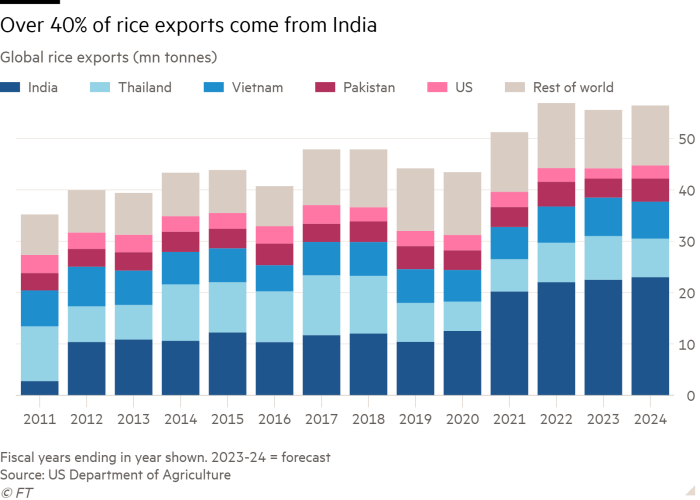

“It’s tough when a country that accounts for 40 per cent of global trade slaps a ban on half of what they export, and duties on the other half,” says Joseph Glauber, senior research fellow at food security think-tank International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and a former chief economist at the US Department of Agriculture.

The immediate consequences of the July ban have been panic-buying among consumers in Asia and North America and responsive measures from other governments in major rice-producing nations.

Now, with India’s rice harvest under way, net importers are hoping for better than expected yields that could prompt the government to ease restrictions. But an election is looming in the south Asian country and food prices are a red-button issue for Modi. The El Niño weather phenomenon, associated with heat and drought across the Pacific Ocean, also threatens to damage output next year as growing conditions may be too dry.

Analysts warn that if India maintains its current restrictions, and other producers follow, the world is on track for a repeat of the 2008 rice crisis, when a contagion of protectionist policies contributed to rice prices tripling in six months, driving inflation across the globe and sparking civil unrest in north Africa, south Asia and the Caribbean.

This time the crisis could be worse, however, as soaring demand, driven by population growth, collides with the effects of ever more extreme climate change.

Rice prices are surging beyond India; the benchmark rice prices in Thailand and Vietnam, the world’s second and third largest rice exporters, have risen 14 and 22 per cent since India imposed its ban.

Arif Husain, chief economist at the UN World Food Programme, points out that the countries likely to be worst affected are already suffering from a litany of woes: sky-high food prices, soaring debt and depreciating currencies.

“When you look at the cumulative effect, you’re essentially talking about a staple commodity not being affordable for millions and millions of households,” he adds.

Hoarding, stockpiles and riots

India has been here before. It was the first to react in 2007 when the price of food staples, such as wheat and maize, rose sharply as poor weather threatened yields.

Rice was in abundant supply, but upward pressure on food prices panicked governments. New Delhi swiftly imposed export restrictions.

Vietnam — then the world’s second biggest rice supplier after Thailand — followed suit and imposed a ban in January 2008. International prices soared, reaching a record high of $1,000 per tonne, as smaller exporters such as Egypt and Pakistan imposed similar bans, farmers hoarded and governments and shoppers stockpiled.

Frederic Neumann, chief Asia economist at HSBC, remembers supermarket shelves in Hong Kong being emptied of rice. Elsewhere, hungry citizens took to the streets. In Haiti, food riots in April 2008 toppled the prime minister, Jacques-Édouard Alexis.

The anger over food prices lingered and eventually coalesced with political discontent, contributing three years later to the Arab Spring, in which four Middle Eastern and north African leaders were overthrown.

This is a lesson many of today’s politicians have taken to heart. In India, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party has made controlling food prices a priority ahead of a series of electoral tests. Food inflation has long been a politically sensitive issue in the country and rice is its most consumed staple.

Prices of the grain had risen 11.5 per cent in the year before the ban on exports was introduced, according to the government, with exports surging over the same period. The cost of other Indian staples such as tomatoes and onions has also risen in recent months as a volatile monsoon season has disrupted agricultural production.

India’s government has defended the ban as a necessary step to protect domestic food security amid worrying inflation, and poor harvests exacerbated by weather that scientists say has become more erratic due to climate change. Many of India’s 1.4bn population continue to struggle with poverty and malnutrition, with about 800mn people eligible for free food grains.

“There’s extra precaution being taken because state elections are around the corner and next year national elections,” says Avinash Kishore, a senior research fellow at the IFPRI in New Delhi. With global oil prices also rising, he adds, “they don’t want a double or triple whammy” as voters head to the polls.

For India’s rice farmers, however, the export ban is a heavy blow.

Sandeep Kumar, 37, and his uncle, Satish Kumar, thought they were in luck after India’s fertile northern state of Haryana avoided flooding that had destroyed crops elsewhere in the country.

Then Modi banned exports of the non-basmati rice the Kumars had cultivated in expectation of strong global demand. Prices rapidly tumbled in the open market, according to Satish. “The government doesn’t value the hard work of the farmers,” he says, speaking from a barn surrounded by green and yellow fields near the city of Karnal. “It has its eye on elections and doesn’t want the rice prices to go up.”

Other critics of the policy argue that the abrupt ban will hurt the country’s reputation as a reliable global trading partner. Under Modi, India has sought to cement itself as a leading global power by expanding trade ties and negotiating free trade agreements with other large economies.

Kirti Kumar Dawar, who runs rice exporting company Jaishree Exports in Haryana, says that he had to retrieve nearly 20 containers of rice, around 450 tonnes in total, that were already in a port for shipping to the Middle East when the ban was announced.

His clients in the region have since “gone silent”, he says, adding that the business will not be able to survive much longer without making global sales. Dawar says he understands the government’s concerns about food security, but “the knee-jerk reaction is wrong”.

The argument has support. “It takes the exporters years to develop the market,” says Ashok Gulati, an economist and longtime adviser to the Indian government on agricultural policy. “This not only upsets the exporters in your own country, it also upsets the importers who will say . . . you are handing over the market to the competitors.”

On the brink of crisis

India’s move has also drawn criticism globally. The IMF called on New Delhi to reverse the “harmful” step, and the US and other countries at the World Trade Organization last month reportedly questioned the need for restrictions while India’s public stocks, they say, are adequate.

One of the main concerns is that the ban on rice exports has the potential to have bigger reverberations than the previous crisis.

Not only has the country’s share of global rice exports grown, but the amount of rice traded around the world has doubled from about 5 per cent in 1999 to more than 10 per cent today, according to data from the US Department for Agriculture, analysed by HSBC.

This makes global contagion more likely, according to HSBC’s Neumann, who says “the risk is certainly there of a repeat of what we saw in 2008”.

“We are becoming more reliant on traded food to secure food supplies for individual populations,” adds Neumann. “But at the same time, we’re also seeing protectionist tendencies growing in the global trading system. And that combination is not very healthy.”

Other countries in Asia are following India’s lead. At the end of August, Myanmar, the world’s fifth-largest rice exporter, announced it would also ban exports of the grain for “about 45 days”. Days later, the Philippines introduced a price ceiling on rice in an effort to dampen rising consumer costs.

Rising rice prices are a significant obstacle for central banks in Asia trying to tame inflation. The Philippines’ and Vietnam’s consumer price indices…

Read More:The return of the rice crisis

2023-10-23 04:00:44