The “Chinese century” is over.

After all the prognostications, projections and proclamations of the past 20 years asserting that China would soon overtake the U.S. as the world’s dominant superpower, the People’s Republic is now facing twin perpetual headwinds, and has no realistic options for countering either of them.

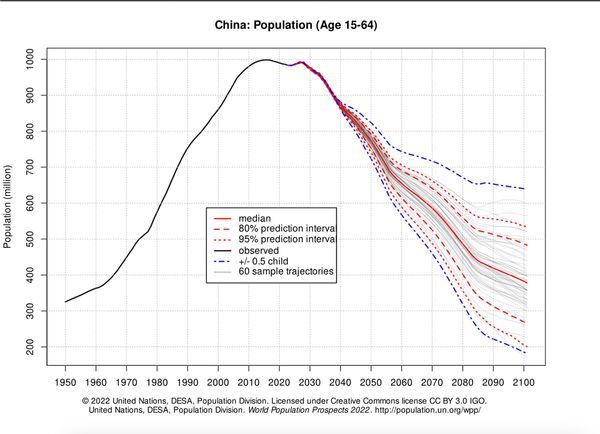

The first could accurately be described as the strongest long-term force driving the fates of all great powers: demographics. What was, for many previous decades,China’s ultimate advantage — its never-ending supply of working-age laborers — peaked at almost exactly one billion people in 2010, according to the Chinese census. The next census, in 2020, revealed that for the first time since China’s economic liberalization in the 1970s, the working-age cohort had shrunk, decreasing by more than 30 million. The U.N. estimates that this group will continue to contract, dropping to 773 million by 2050. (In other words, between now and then China is likely to lose a number of workers larger than the entire population of Brazil.) The under-14 population will also fall in that same period, from just over 250 million in 2020 to a median projection of 150 million in 2050. Not only will the workers be disappearing, but nobody is expected to replace them.

(United Nations)Every age-related trend in China is going in the wrong direction. The nation’s median age, once well below the Western world’s, is now older than America’s and headed further north with every passing year. Deaths outnumbered births last year for the first time since 1961. The fertility rate, which normally must be at 2.1 children per adult woman just to maintain a steady population, has slipped to below 1.1 — a figure made worse by the fact that, unlike in virtually every other country on the planet, China doesn’t have a relatively even gender split in its adult population, the long-term result of male favoritism combined with the central government’s infamous one-child policy. Basic math dictates that tens of millions of these “extra” men will never start families of their own. To compound the problem even further, women in China have indicated lower interest in having children than ever before; more than two-thirds have expressed “low birth desire.” According to Prof. James Liang of Peking University, fertility rates in Beijing and Shanghai have fallen to an astonishing 0.7, “the lowest in the world.“

(United Nations)Every age-related trend in China is going in the wrong direction. The nation’s median age, once well below the Western world’s, is now older than America’s and headed further north with every passing year. Deaths outnumbered births last year for the first time since 1961. The fertility rate, which normally must be at 2.1 children per adult woman just to maintain a steady population, has slipped to below 1.1 — a figure made worse by the fact that, unlike in virtually every other country on the planet, China doesn’t have a relatively even gender split in its adult population, the long-term result of male favoritism combined with the central government’s infamous one-child policy. Basic math dictates that tens of millions of these “extra” men will never start families of their own. To compound the problem even further, women in China have indicated lower interest in having children than ever before; more than two-thirds have expressed “low birth desire.” According to Prof. James Liang of Peking University, fertility rates in Beijing and Shanghai have fallen to an astonishing 0.7, “the lowest in the world.“

In Japan, economic stagnation produced a period that was called the “Lost Decade.” That stagnation eventually persisted so long that some began to refer to it as the “Lost Generation.” In China, an even more ominous buzz-phrase has become popular online: The “Last Generation.”

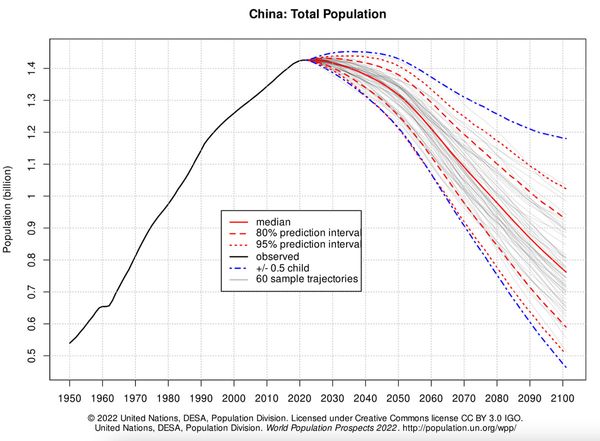

Much has been made of the difficulties China will face in attempting to manage a rapidly-shrinking workforce against a rapidly-growing retirement age population, which is projected to double by 2050. But that issue may actually be preferable to what is likely to happen afterward, or perhaps sooner if some of China’s older population doesn’t wind up living as long as expected. Here are the UN estimates for China’s total population between now and 2100:

(United Nations)Notice the lower-end expectations at the end of the century: 600 million, 500 million, perhaps as low as 450 million. Even the median projection puts the number at around 750 million. This is not just a rogue estimate by a single U.N. agency — the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences has issued an extremely specific prediction of 587 million. If you think China has ghost cities now, imagine that vast nation with barely one-third of the population it has today. What will happen to property values in a country where between 50 and 70 percent of its people have disappeared? What will happen to tourism? To retail? So many articles have been written about what happens when a modern society grows “too old,” as has happened in Japan and Germany, among others. But how many have been written about what happens when the majority of a modern society vanishes altogether?

(United Nations)Notice the lower-end expectations at the end of the century: 600 million, 500 million, perhaps as low as 450 million. Even the median projection puts the number at around 750 million. This is not just a rogue estimate by a single U.N. agency — the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences has issued an extremely specific prediction of 587 million. If you think China has ghost cities now, imagine that vast nation with barely one-third of the population it has today. What will happen to property values in a country where between 50 and 70 percent of its people have disappeared? What will happen to tourism? To retail? So many articles have been written about what happens when a modern society grows “too old,” as has happened in Japan and Germany, among others. But how many have been written about what happens when the majority of a modern society vanishes altogether?

To make matters worse, if that seems possible, all these numbers rely on official Chinese statistics, and the government has likely been overstating them. According to an extensive examination of different sets of books by University of Wisconsin Prof. Yi Fuxian, it’s possible to find the “fudging” effects by comparing local and provincial data to that published at the national level.

If you think China has ghost cities now, imagine that vast nation with barely one-third of the population it has today. What will happen to property values in a country where between 50 and 70 percent of its people have disappeared?

“For the official statisticians,” Yi explains, “the primary school enrolment data should be reliable because public education covers every Chinese child. They were wrong, however, because primary school enrolment data in China is often inflated so that local authorities can claim more education subsidies from Beijing. … According to a report by CCTV on January 7, 2012, the Jieshou city in Anhui province reported 51,586 primary school students, when the actual number was only 36,234, allowing them to extract an additional 10.63 million yuan (about $1.54 million) in state funding. On June 4, 2012, China Youth Daily reported that a middle school in Yangxin county, Hubei province reported 3,000 students, while the actual number was only 700.”

In a country as large as China, what do these figures look like when aggregated to a national scale? According to Yi, government data “showed that China had 366 million new births” between 1991 and 2010, “but the group aged 0-19 in the 2010 census was only 321 million.” In other words, either 45 million of those children had died between birth and the census, or they never really existed in the first place.

That was just one cohort, in one census, but it’s hardly the only example. “In 2010, the population aged 3-14 was only 169 million, according to the 2010 household registration database, and 176 million, according to the 2010 census,” Yi continued. “Yet, according to the Chinese statistics bureau, there were 210 million births in the 1996-2007 period.” Again, either China has secretly experienced the greatest wave of mass child deaths that the world has ever seen, or the birth-rate numbers were always grossly exaggerated.

China’s demographic headwinds, therefore, may be hurricane-strength. To be fair, most major nations in the West also face declining birth rates and aging citizens. The enormous difference in projected demographics, at least in many of those cases, comes down to immigration. Even with a current fertility rate of only 1.6, the U.S. population projects to reach roughly 400 million by the end of the century, according to the U.N.’s median estimate. East Asian countries tend to have much more restrictive immigration policies, but nowhere is this as true as in the People’s Republic. Since 1950, which is as far back as the data goes, China has never experienced a single year of net positive migration. Ever.

As previously mentioned, Beijing faces not one but two enormous burdens going forward. The second should not come as much of a surprise, as it was intertwined with China’s population burst during all the good years: the economy.

Yes, the mighty Chinese economy, the boomiest boom that’s ever boomed… is going to become a big, big problem. Much of this problem will, of course, be caused by the enormity of the demographic crunch. But there are specific details that will amplify the impact of that crunch. A whopping 70 percent of Chinese household wealth is held in real estate. Seventy. Percent. (The comparable number in the U.S. is less than half that.) The demand for investment properties has been so high that China’s construction eruption simply cannot be reasonably compared to those that have occurred in any other major economy, even ones that have experienced giant housing bubbles of their own. As this graphic from the Reserve Bank of Australia shows, “residential gross fixed capital” as a proportion of GDP is close to 20% in China — the comparable proportions in Australia, Japan, South Korea and the U.S. are all around 5% or less.

Keep in mind that China’s population is shrinking, and will continue to do so with increasing velocity. According to the World Bank, home price-to-income ratios in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen exceed “a multiple of 40;” the same figure is “only” 22 in London and 12 in New York, two notoriously expensive cities in the West.

It is likely impossible to overemphasize the potential economic damage that will likely ensue when previous decades of population growth, urbanization and the frenzied real estate investment that has accompanied them run into the brick wall of new decades with consistently fewer buyers — and that doesn’t mean “fewer buyers” in the normal sense of a bubble popping, but the literal absence of hundreds of millions of buyers over time. What will happen as those aforementioned ghost cities begin to multiply? And perhaps the more important question: How can China possibly make its all-important transition to a consumer-based economy when consumers as a whole have shoved so much of their wealth into properties that will often end up being worthless? How in the world is this supposed to work? How could it work?

That consumer transition becomes more necessary every day, because China has no other realistic option for productive growth moving forward. For years, Beijing has obsessively pushed economic activity toward investment, which sounds appealing at first simply because of the connotations of the word. But the Middle Kingdom long ago started running up against the law of diminishing returns when it comes to endlessly increasing investment. As Carnegie’s China scholar Michael Pettis explained earlier this year, “China has the highest investment share of GDP in…

Read More:China’s Great Leap Backward: So much for the next dominant superpower

2023-07-30 16:00:00