Every time the real-estate market crashes, people say, “This time is different.” When there’s distress all around, it’s hard to grasp how there could ever be an upside. But with the benefit of hindsight, you can see that if you’d had enough money when things got bad, you could have made a killing by taking the other side of the bet. Let’s go back to 2009. There was calamity as far as the eye could see: bank bailouts, paralyzed credit markets, a toxic heap of mortgage debt crushing the world economy. Scott Rechler, having fortuitously sold his family’s real-estate company at the top of the market to a competitor for $6 billion, decided it was a good time to go shopping for office buildings. After raising more money from sovereign wealth funds, other institutional investors, and wealthy private individuals overseas, he went on an opportunistic buying spree. Over three years, he spent $4.5 billion on Manhattan office acquisitions. By 2020, his company, RXR, was a major office landlord with more than 22 million square feet of space in the city.

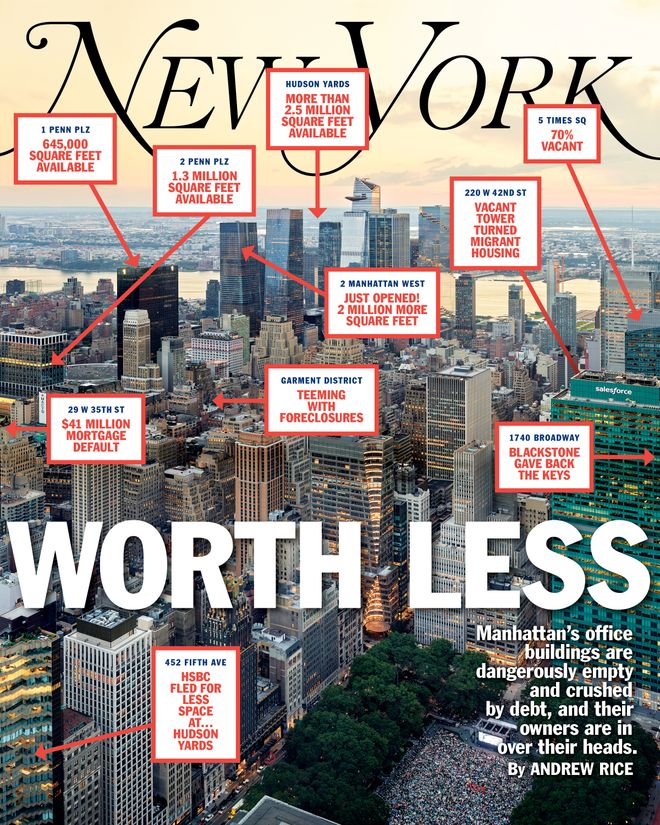

Today, three years after the pandemic emptied office buildings nationwide, Rechler has been forced to reckon with the possibility that the buildings that were worth so much not so long ago may now not even be worth keeping. Corporate tenants are typically locked into multiyear leases, which guarantee stability in the commercial real-estate market for a time. But every month, more leases expire, giving tenants an opportunity to rethink their space, and every day, employers are staring at empty desks. Many companies, which had been trying to squeeze more workers into less space for years, are not renewing. That leaves an office landlord facing hard choices. What should Rechler do, for instance, with 5 Times Square, a million-square-foot building that 20 years ago was a gleaming centerpiece of 42nd Street’s revival? After the departure of its longtime anchor tenant and major renovations, it’s currently close to empty.

Not long ago, real-estate industry leaders were urging the city’s workers to return to their office buildings. Rechler told me in 2020 that it was a “civic responsibility.” They’ve since surrendered to the changed reality. Sometimes tenants are downsizing and upgrading to more expensive spaces; sometimes they are economizing under the guise of offering flexibility. From the landlord’s perspective, motive hardly matters — space is space, and it’s got to be rented. Add in sharp hikes in interest rates, which make refinancing a huge commercial mortgage a potentially ruinous proposition, and you have a crisis that threatens not just the solvency of office buildings but the loans that are attached to them and the banks that hold them and, by extension, the whole economy.

“We’re crossing a chasm,” Rechler told me when I visited him at his office at 75 Rockefeller Plaza in early June. More than any of the city’s other major landlords, he’s been warning of what he calls a “slow-moving train wreck.” Like it or not, everyone suffers if banks collapse. And if you are a New Yorker, you have a great deal at stake in the market because of the enormous public revenue offices generate — 21 percent of the city’s property-tax levy — money that goes to pay for schools, public housing, fire trucks, pensions, parks, and so much else that makes life in New York tolerable.

According to Cushman & Wakefield, Manhattan’s office-vacancy rate is around 22 percent, the highest recorded since market tracking began in 1984. When you include sublet space, more than 128 buildings in Manhattan currently list more than 200,000 square feet of space as available for lease, according to data from the firm CoStar. The available space in these buildings alone amounts to more than 52 million square feet: the equivalent of more than 40 skyscrapers the size of the Chrysler Building. Certain areas and building types are particularly endangered — the Garment District lofts once favored by tech start-ups, the generic glass gulch of Third Avenue in the 40s and 50s — but the pain is widely distributed. Many large property owners are now performing triage, trying to determine which buildings are still worth anything like what they paid for them. In Rechler’s case, this reassessment has taken the form of a process he calls “Project Kodak,” after the once mighty film-and-camera company. He classifies buildings that are worth saving as “digital.” The duds he deems “film.”

Rechler, 55, is a bald, blunt real-estate dynast. He comes from a Long Island family that turned a small fortune made by his grandfather — he patented the folding aluminum beach chair — into a very large one, mostly by building industrial and office parks in the suburbs. When he was in his early 30s, Scott pushed the family company into Manhattan real estate before he sold it in 2007 to SL Green Realty Corp., which is now Manhattan’s largest commercial landlord. He took his peak-of-the-market profits and set out to build RXR on his own. Like any successful commercial-property owner, he has hedged his company’s risks by partnering with other real-estate firms, spending other people’s money — in his case, mostly from overseas investors — and selling off bits and pieces of his portfolio at advantageous moments.

Rechler said he began Project Kodak from a position of relative strength, which has allowed him to be cold-blooded when it comes to culling the buildings he owns. Of course, he would say that: Commercial real estate is a bluffing business, so it is rare for its players to admit they are in trouble. All the big landlords — SL Green, Vornado Realty Trust, Brookfield Properties, the old real-estate families — are facing the same problem of vacancy and shrinking demand. Where Rechler differs from the rest, though, is in his relative candor about the consequences. “Obviously, when we lose money, it hurts, and in many of these cases we will lose money,” he said. “You need to rise to the opportunity and re-create value.”

Rechler casts himself in the mold of businessmen like Nelson Rockefeller, Felix Rohatyn, Mike Bloomberg, and Dan Doctoroff, who have taken charge in times of distress, at least according to their own mythology. “There’s been a void of leadership,” Rechler told me. Under Governor Andrew Cuomo, Rechler played an influential role on the board of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and he later served as the chairman of the Regional Plan Association. His desk is equipped with a ring light and a microphone for his frequent appearances on podcasts and CNBC, in which he pleads for action from regulators and policymakers. He speaks against a backdrop of graffiti art — a pair of pieces by Mr. Brainwash, collaged images of road signs and Superman and uplifting spray-painted slogans (FOLLOW YOUR DREAMS … NYC IS BEAUTIFUL).

Rechler also sits on a board that oversees the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and has been outspoken about the possibility of economic “contagion” emanating from distressed commercial-real-estate debt. Rechler predicts that within two years, there will be “500 to 1,000 fewer regional banks” owing to failures and forced consolidations. He has been advocating, with some success, for action from banking regulators, who can influence lenders’ decisions when it comes to troubled loans. He wants lenders to loosen up the credit markets, which would benefit the industry in general and Rechler in particular, though his self-interest doesn’t make him wrong. “Some people accuse Scott of speaking his own book,” says one of his real-estate competitors. “But what he says is right on the money.”

“I think raising the alarm is important,” Rechler said. “Government has been really good at responding to crisis. They’ve been really poor at proactively trying to prevent crisis. So we could wait three, four years until our tax revenues are down 20 or 30 percent, and our transit system once again is broke and falling apart, and we have crime on our streets and homelessness in these dark areas where we have vacant buildings, or we could try to get ahead of the game.”

Rechler is confident that, on the other side of the agony, there will be new opportunities for his business and for the city. “I was with Mike Bloomberg yesterday talking about this,” he said. “How anytime anyone bets against New York evolving, they lose that bet.” An inherent part of evolution, though, is elimination. Some real-estate companies will not survive the crisis. Office buildings will end up demolished. A group of people who have long owned the city, both literally and politically, could end up making less and mattering less. This time might really be different. That may not sound like a tragedy; few New Yorkers miss their sweaty daily commutes, their crammed open-plan galleys, their plastic-packed salads. But what is this city if its skyline is now obsolete?

Rechler (and his Mr. Brainwash) in his office at 75 Rockefeller Plaza.

Photo: Bobby Doherty

Let’s start excavating the numbers. In normal times, Rechler said, making a value assessment is more straightforward. The industry’s key metric is a figure called the “cap rate.” To understand the cap rate, you have to think of an office building the way a real-estate investor does: not as a steel-and-glass object but as a snowcapped mountain that creates a river of cash. To calculate the cap rate, you take the cash flow and subtract expenses. Whatever is left is net operating income. Divide that by the building’s market value as an…

Read More:The Real Cost of New York City Office Real Estate

2023-07-17 12:00:04